Defining 'community' in the digital age

If I asked what the term “community” means to you, what would you describe?

Maybe you’d talk about a sense of belongingness or togetherness, or of being able to rely on other people when you need something. Some of you might think about a sport or activity that connects you with others. Others might mention a geographic element – community as something where we are all in the same physical space or tied together through a connection to a place.

We heard all of these characteristics when we talked with focus groups of older adults about what community means to them these days and how community influences the decisions they make about their health. That question—and the conversations that arose from it—was informed by our polarizing national discussion about the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as discussions about our social (dis)connection and man’s shortsightedness in being able to care for others beyond himself.

But in debriefing after these groups, I noticed that we had heard very little about the presence of digital communities in the lives of our participants. I wondered, in our 21st century information age, where more of us than ever before are interacting online, what features make a digital community feel like a community? Are these features similar or dissimilar to our current experiences of non-digital communities?

An exact conceptualization of what makes a community has been difficult to establish. Classical sociologists (such as Tönnies, Durkheim, Weber) considered community both a unit of social organization and something with an impactful quality, implying that our social relationships to one another had meaning and attachment. 20th century community sociology further developed these perspectives using theory from fields like human ecology to suggest our tendency for togetherness was a result of our need to survive.

Present perspectives in community theory emphasize that today’s communities often involve a form of geographic separateness (e.g., that we are not all in the same physical space together) and elements of our identities (e.g., to use age as an example, as a 27-year-old, I relate more to the generational experiences of Millennial and Gen Z’ers then I do with Baby Boomers and Gen X’ers). In my opinion, we can’t extract technology away from enabling and influencing this. A few months ago, I attended an online leadership conference; hosts and participants came from companies all over the world. When each speaker was introduced, the call’s ‘chat’ would explode with a waterfall of hashtags from members of that person’s company. It was a striking sight.

I wondered how conscious these participants were of their creating and reinforcing in each other a shared sense of community around an employer. For me, perhaps more existentially, I wondered if it said something about me and my relationship to my employer that I was not immediately agog to type #AgeLabBestLab or #iworkforMIT as fast as my digits could carry me?

Now, let me take you back to 2005. I was in the 6th or 7th grade. I had grown up on Disney movies and the Disney channel (hello Jonas Brothers!) and was pumped to hear about a new multiplayer online game developed by the Disney Company that was set in a virtual Disneyland. I couldn’t get enough of playing that game. My attachment to VMK was a completely virtual one; my fellow players online were all complete strangers. And I was constantly forming meaning about what it meant to be a VMK player – the kinds of quests you did, the type of ‘guest room’ décor you had, or if you typed in a certain way as to circumvent Disney’s limited dictionary available to chat with other people. VMK may have been an early example of the sense of community that can develop around the digital entities that mean something to us and our identities, subsequently connecting us to each other. Massive communities exist now around online games, and as well as around individual content producers like streamers and influencer who play the games themselves.

Dr. Toby Lowe at Northumbria University defines community as a group who share an identity-forming narrative. He writes that communities are individuals in groups making a choice to participate in the making and re-making of the storytelling that defines the archetypes and character traits of the community, such that these stories become a part of who they are.

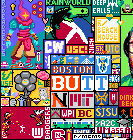

Earlier this year, the popular social networking site Reddit hosted what was called r/place. The site had previously hosted this event, often called a “collaborative project” or “social experiment,” one other time in 2017. This year, it was a multi-day event where Reddit users could edit a blank online canvas by changing the color of a single pixel. Each user had a 5-minute wait between each pixel-placing. Millions took to placing pixels contributing to displays of fandoms, logos, national flags, and many other representations of online, in-person, tangible and less tangible communities.

My partner and I got addicted to placing pixels all weekend. We found ourselves coordinating with other participants from the MIT and Boston subreddits to design and defend our corner of Internet art representing the two communities we love the most. If you want to play a little “Where’s Waldo?” check out this screenshot of the final canvas and see if you can find MIT on the far-left edge of the page (upper left of the Linux penguin). In this case, we were interacting through chats and posts with other people and actively participating in the identity-forming stories we tell ourselves about what our community stands for and how it should be represented.

The next iteration of sociological theory and research on community will have to evolve with the advent of augmented and virtual reality and related technologies, which may serve to redefine our interactions with one another and change how we think about digital social connection. I learned from that leadership conference that maybe finding digital community will mean having a previous familiarity or rapport with that entity outside of the digital workplace. As I’m reminded from the field of netnography, a field of research examining our interactions online, online communities from games like VMK can be case studies for how digital communities co-create their own language, culture and meaning in their interactions with one another. And in the case of r/place, well, it turns out it is very possible to create a deep sense of collectivism and belonging to one another through a pixel.